27 May Preparing Post-Millennials for the Second Machine Age

45 % of today’s jobs will disappear by 2035.

Sure, job titles have come and gone over the centuries as we progress technologically, but this time we’re dealing with an entirely new animal. Computers are starting to replace us in jobs we thought were only human and pressing down the marginal cost in production towards zero. Zero marginal costs means is that the production of an extra copy has no cost associated with it. Examples are digital replica of a musical file or newspaper article, or tax preparation software where the cost of doing tax 5 years is equal to one year whereas a CPA would charge extra for each additional year. Some people would even include energy production after the investment in equipment for generating (solar, wind) and storing (batteries). This dynamic decouples humans from the value chain and creates few winners and many losers. The best present-day example is possibly how computing went from being a human task to a computerized task, hence the word computer.

The picture above is what computers looked like 60 years ago. I haven’t met any of these women, but I can guarantee you they have a much better grasp at trigonometry and calculus than I will ever have. And yet I wonder how they would react if I told them I can pull out a rectangular device from my pocket that gives access to most information ever known to man. Or communicate freely with people halfway across the world. How would they react if I told them this device would link us together in ways that would help organize political uprisings or aid in disaster areas? I wonder how they would respond if I said that a child living in sub-Saharan Africa is more likely to have access to a computer far better than those of their superiors at NASA than he is likely to have access to adequate food or sanitation.

The technological revolution that is going on right now is having such pervasive effects that it is upending how we live, how we work and eventually how we organize our society.

A lot of literature and scholars are addressing these issues and what it means to be human in this emerging digital economy. Two books in particular have fascinated me recently as they complement each other by writing about the two most important consequences of this second machine age.

The first book is what I would like to refer to as the first parenting book for futurists: “The Curiosity Cycle” by Jonathan Mugan. But really, if you’re just a geek expecting your first child and are hip to the idea that your child’s world will differ significantly from our own, you might want to clear some space in your bookshelf between Kurzweil and Spock (the doctor, not the pointy ear guy!) Jonathan Mugan’s academic background is in developmental psychology as well as in computer science and he researches how to teach machine to learn like children. He is an expert in identifying how children learn differently than machines. Brynjolfsson and McAfee’s The Second Machine Age are more concerned with the societal and economic aspect of the digital economy, which is linked to automation and well as economies of scale.

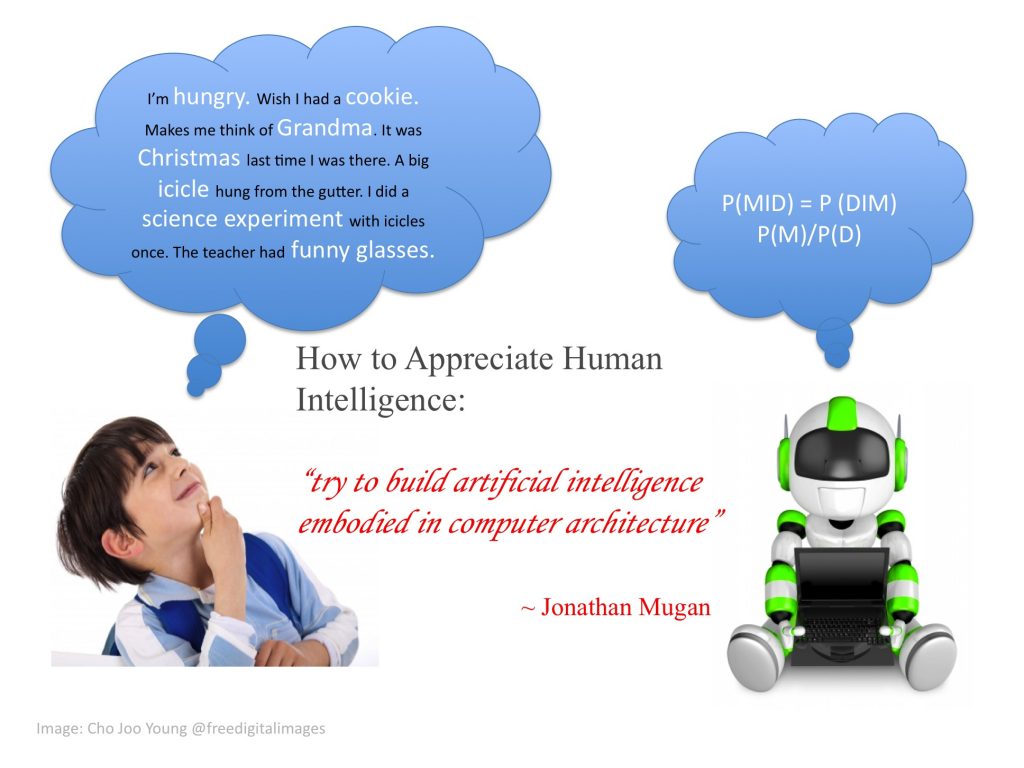

Children learn by sensory input that helps them individuate concepts of things in their surroundings. They build models upon these and test these models in their everyday activities. This process goes through several iterations as they deepen their understanding of their environment. Mugan says that curiosity is at the root of human learning. When human learning is driven by curiosity it leads to flexible and adaptive thinking which is different from the brittle systematic thinking that smart machines can do. And curiosity driven learning is also so much more relevant.

Children are motivated by questions and hypotheses, and will search for data based on these questions. Their data will often be incomplete, but the limitation is often what helps humans induce relevant answers.

Problem solving is one way for children to test their models. Mugan wants us to inspire the natural wonder kids have for things we take for granted. A hot gender topic these days is whether girls should be discouraged from toys that allegedly promote princess obsessions. Mugan jumps elegantly over this thorny debate, and suggests instead that princesses and their castles may open their iron gates to discussions about political systems like monarchy and arranged marriages. Seeing how problems have been solved differently in other time periods should strike a chord in futurist parents since by giving children a sense of historic progression, we may nurture an appreciation for the idea that also the future will look radically different.

Humans learn by association and drawing analogies to past experiences. Our thought processes don’t typically follow a linear agenda, but works intuitively and makes linkages between ideas that don’t follow common algorithms. I have something called synesthesia, which is a neurological phenomenon where sensory input sets off two unrelated cognitive pathways. So for me when I learned numbers and letters for the first time they literally came color-coded. I could never understand why others didn’t see that A is always blue or S is always white. Synesthesia is different from associations that are based on past experiences. But neither associations nor synthestetic combinations give impetus to machine learning which is limited to pre-planned algorithms and formulas.

Humans learn by association and drawing analogies to past experiences. Our thought processes don’t typically follow a linear agenda, but works intuitively and makes linkages between ideas that don’t follow common algorithms. I have something called synesthesia, which is a neurological phenomenon where sensory input sets off two unrelated cognitive pathways. So for me when I learned numbers and letters for the first time they literally came color-coded. I could never understand why others didn’t see that A is always blue or S is always white. Synesthesia is different from associations that are based on past experiences. But neither associations nor synthestetic combinations give impetus to machine learning which is limited to pre-planned algorithms and formulas.

Until recently associative learning has been uniquely human and driven more by curiosity than data, which leads to much different results than algorithmic searches. However, we should not be too comfortable thinking that computers suck at pattern recognition and have trouble learning by analogy. By applying hypothesis testing and natural language processing of vast quantities of data, computers are learning to replicate cognitive operations we once had monopoly on and will eventually make inroads into traditionally human enterprises that draw more on creative and visionary abilities. Just ask IBM’s Watson or Automated Insights.

But when it comes to insights that are based on sensorimotor development, humans still have a literal and figurative leg up. Mugan explains that “Physical experience is the Foundation of Knowledge” and that “One way to gain deep appreciation for human intelligence is to try to build artificial intelligence embodied in computer architecture”.

Scenarios about the technological singularity or our future robotic overlords are often based on projections of Moore’s Law, the stipulation that various computer capabilities (storage, memory, processing power etc.) doubles every second year. But even if Moore’s Law operates on an exponential scale, it is mainly concerned with a difference of degree rather than of kind. For humans to replace humans they have to pose a change in kind, which has led to Moravec’s Paradox, the idea that for all high-level reasoning we can get out of our yet-to-be overlords, low-level sensorimotor skills still require enormous computational resources.

This dilemma is actually a great source of humor. When I upload a picture of my daughter and myself to Google Image search, Google thinks we look like food. And I guess to certain predators we still do, but if Google instead was a species under humans in the food chain, it would go extinct fast. If my survival strategy involved eating little mini-googles for breakfast, Mountain View, CA would quickly become a pretty desolate place because Google doesn’t have the long evolutionary history that makes it able to instinctively recognize threats, such as faces.

This dilemma is actually a great source of humor. When I upload a picture of my daughter and myself to Google Image search, Google thinks we look like food. And I guess to certain predators we still do, but if Google instead was a species under humans in the food chain, it would go extinct fast. If my survival strategy involved eating little mini-googles for breakfast, Mountain View, CA would quickly become a pretty desolate place because Google doesn’t have the long evolutionary history that makes it able to instinctively recognize threats, such as faces.

But our main challenge is not the direct competition with smart machines, but how these technologies break down barriers to competition between people. A slew of literary endeavors these days deal with the growing wage gap between wage earners and capital owners. The Second Machine Age is the story of these inequities and how they evolved. Authors Brynjolsson and McAfee delineate two new dynamics and distinguish these as “bounty” and “spread”. Bounty refers to the endless opportunities in products and services helped by digital creation and reproduction. Reproducing a digital product is cost free, but secures a consistent revenue stream for the creator of said product. Think about the music industry for a moment. Jay-Z and his people make an extra dollar for every download of his latest hit while incurring no expenses. So there are no human workers that benefit in his growth model. This is the case for any product or service where consumption have ceased to reflect human labor input. Since the barriers for creating and publishing new content is so low and reproduction cost free we get an economy of what Jeremy Rifkin calls “prosumers”, or the blending of consumers and producers. So we continue to have a lot of creative “prosumers” and can continue to get a lot of good music, but only Jay-Z gets to reap money from it as less successful musicians are pressured to let people stream their music for free. An economy that allows only 0.001 percent to reap most of the proceeds while the rest scavenge for second place in not sustainable in the long run. And it looks like the music industry is becoming the model for any other industry where ubiquitous replication is possible.

The problems discussed in both of these two books got me thinking more deeply about what value creation really is and I wonder if we’ve been too blind to look beyond the white collar/ blue-collar dichotomies. At panel debates and conferences where the authors discuss these topics, you rarely see people in caretaking position who have created value for decades – but outside of the traditional economy, homemakers, caretakers, community volunteers etc. Think of all the work that has been done – or needs to be done – that are not reflected in our current GDP. What about all the “green collar” clean up jobs or jobs to retrofit our homes and infrastructure to prepare for renewable energy consumption and production. Imagine the need for un-robotized “human touch” professions that will provide nursing and care to aging Boomers when they finally realize eternal youth is a false illusion created by opportunistic life coaches and thought leaders who want to sell books.

There is no doubt we are raising a generation that will have to coexist with smart machines.

Technology helps children become either active producers or passive consumers in the new economy, and it is how we approach it as parents that will make the difference. We can let them play games where the game structure is created for them, or we can teach them basic coding skills and introduce them to games where they control more of the creative process. We can let them mindlessly consume cable sitcoms or we limit their screen time to educational experiences. We can continue to feed children shallow knowledge through rote memorization or we can teach them critical thinking and curiosity driven learning. And finally, as parents or educators we can continue to drill and test children in areas where computers are inevitably better or we can help them build comparative advantages that complement rather than compete with the smart machines.

But finally we have to realize that this new technological revolution is less about how machines will replace us and more about how we define, distribute and allocate value as a society. Do we want to give musicians a chance even if they can’t compete with Jay Z and Taylor Swift? Let’s reward them for what they produce. Do we want to prevent our nursing homes from being taken over by robotic nurses while humans go unemployed? Let’s make it viable for employers to hire humans instead. Do we want to incentivize cleaning up the waste that is currently killing marine wildlife in our shores and oceans? Let’s move venture capitalists and philanthropists over in those directions. Our robots will only become our overlords if we don’t use them to our advantage instead of curse. Or to quote Isaac Asimov laws:

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey the orders given to it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.